1740

The house that would become Raynham Hall Museum was built sometime before 1738 as a two-story frame house with central brick chimney, gable roof, flush siding of wide boards and a five-bay façade with an entrance in the middle. The house contained four rooms — two on each level — with a garret or attic under the roof. The first floor consisted of a “hall” and “parlor” that flanked a narrow passage with a winding staircase built around the chimney. On the second floor were two “chambers” that corresponded to the hall and parlor below. Fireplaces opened into all four rooms from the central chimney.

Around 1740, Samuel Townsend built a lean-to section on the north side, or rear, of the house. The addition, which increased the number of rooms to eight, included a kitchen and storage room on the first level and chambers above. The shed roof of the lean-to section extended the rear slope of the main gable roof, creating the distinctive “saltbox” outline.

Architectural and documentary evidence suggest that at least one of the first-floor rooms featured wall paneling. The original parlor fireplace wall appears to have had paneling that extended from floor to ceiling as well as a decorative mantel and overmantel. The mantel, overmantel and parts of the paneling are today incorporated into one of the restored Colonial-period rooms.

No substantial changes were made to the house during the remainder of the eighteenth century. The museum’s collections include a pencil sketch of the house, dating to around 1830, that shows a one-story porch extending the full breadth of the façade. The porch, which must have been added shortly before 1800, seems to be the only improvement made by the Townsends. The sketch clearly depicts the paneled Dutch door that is in place today and dates back to the mid-18th-century house.

18th Century Hall

This room would have been the primary gathering place for Samuel, Sarah and their children, especially during the Revolutionary War, when the family was likely forced to relinquish the more formal parlor to the British occupiers. In this place, the family would have engaged in a variety of activities including reading, writing, domestic tasks such as sewing and spinning, and taking meals. Samuel might also have used the hall occasionally as an adjunct office, though it is likely he also kept a principal workplace closer to the waterfront.

Objects of special note in this room include the 18th century Dutch-style cupboard, or “kas,” most likely made on Long Island or in Brooklyn, and etched glassware original to the Townsend family.

18th Century Parlor

In the 18th century, the “parlor” was the most formal room in the house, used for receiving and entertaining guests. As the “best” room, the parlor contained the Townsends’ most expensive furnishings.

The secretary – a desk with glass-fronted bookshelves – on the far wall was owned by eldest Townsend son Solomon, and family lore says that it travelled with him across the Atlantic many times onboard the ships he captained. The tall clock in the corner was said to have been a wedding present to Solomon and his wife from his father-in-law.

When the house became Oyster Bay’s British headquarters during the American Revolution, the room’s “guests” were Queen’s Rangers commander Lt. Col. John Graves Simcoe and his officers.

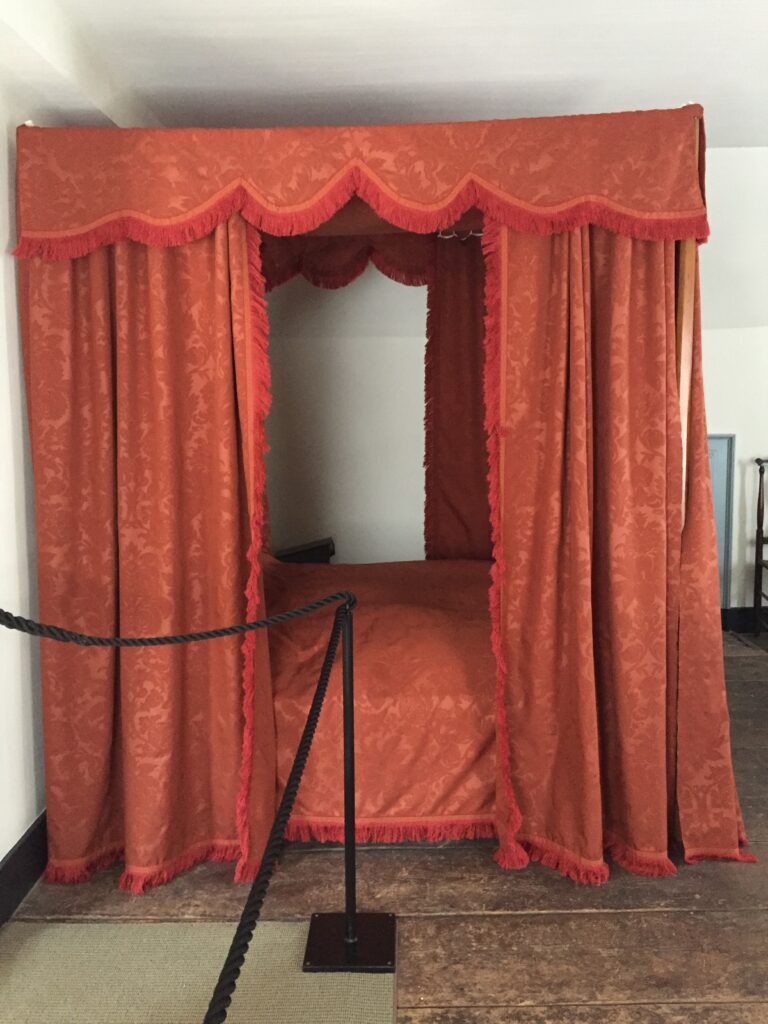

Colonel Simcoe’s Room

Adjacent to the 18th century parlor is a room known to have been used as a bedchamber by Lt. Col. John Graves Simcoe, who would have carried with him as he travelled all the items necessary for his comfort, such as the textiles around his bed and in his windows, a travelling library, china, silver, and even art supplies, since he is known to have been an accomplished amateur watercolorist. One of his guests at Raynham Hall was the charismatic British spymaster Maj. John André, who worked successfully to turn Gen. Benedict Arnold against the Americans, and who was hanged himself as a spy. This room also was occupied by the other commanders of regiments that occupied the Town during the war.

Samuel and Sarah Townsend’s Bedchamber

Samuel and Sarah Townsend occupied this bedchamber. Samuel’s importing and exporting business afforded the Townsend’s access to the type of rich fabrics used in the bed hangings. Not only were the hangings decorative, but they also provided warmth in the winter, and privacy. Due to the absence of closets, pieces of furniture such as the Townsend family high chest of drawers, which is believed to have been made by Sarah Townsend’s father, in Jericho, were used for the storage of clothing and other textiles.

The Townsend Daughters’ Bedchamber

The Townsends’ three daughters, Audrey, Sarah (or Sally), and Phebe would have shared the room across from their parents’ bedchamber. The eldest, Audrey, would have been 21 at the outbreak of the Revolutionary War in 1776, while Sarah would have been 16 and Phebe 13. This room contains two blanket chests made around 1700 in Oyster Bay, and an 18th century walking wheel (used for turning wool fibres into thread or yarn) made by Ambrose Parish, also in Oyster Bay.

The Sleeping Quarters of the Enslaved People

Though we have no record of any space specifically set aside for the use of the people held enslaved by the Townsend family, we are fairly certain that a space such as this one – with a much smaller window than the others, an awkwardly sloped ceiling, and easy access to a startlingly narrow staircase leading to the back of the house, where the kitchen would have been – could easily have been used by enslaved people.

We have interpreted this space as being used in 1779, during the period of the British occupation, by a 23-year-old woman named Susan, her daughters Catherine, age 7, and Lilly, age 5, as well as Elizabeth, or “Liss,” a 17-year-old woman who is known to have escaped with the British when they decamped from Oyster Bay, and a boy of 9 named Jeffrey, whose mother Susannah is recorded to have died of smallpox in that year. These are six of the twenty enslaved people recorded to have been held in the Townsend household.