Guest Post by Elizabeth Fox, Marcia Brady Tucker Fellow in American Decorative Arts at the Yale University Art Gallery

Textile enthusiasts, knitters, and sewing bees: this post is for you!

In December 2023, I presented a “Townsend Talk” on the history and craftsmanship of furniture made in Long Island between 1640 and 1830. One furniture type discussed was the humble spinning wheel. Used widely in Europe by the 13th century, spinning wheels occupied many early American homes, where the production of flax and wool developed as a cottage industry (fig. 1). During the 17th and 18th centuries, colonists often purchased imported fabrics, woolens, and linens from England while the American colonies were prohibited from importing their own finished cloths. However, the Revolutionary War encouraged them to resist British tariffs and express their patriotism through homespun production. Spinning wheels fell into disuse after the 19th century when industrialization made manufactured textiles cheaper and readily available.

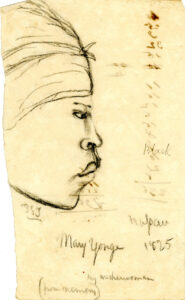

Extant wheels dating from the late 18th and early 19th centuries prove how spinning technology remained unchanged in Long Island until the weaving industry became mechanized. Joiners like the Dominys of East Hampton utilized their wheelwrighting skills to churn out these standard pieces of equipment en masse (fig. 2)¹. Women, including housewives and enslaved servants, generally performed the difficult and arduous task of spinning flax or hemp into linen and wool into thread or yarn. Linen was woven into clothing, bedding, tablecloths, and other textiles for daily use. It offered a ground for young women to practice and improve upon their needlework, as demonstrated in Rebecca Townsend’s 1837 sampler (fig. 3). A “flamestitch” canvaswork pocketbook made for Samuel Townsend (fig. 4) reveals the application of linen and wool. The Townsend women who sewed these highly personal objects either used imported or homespun linen and wool.

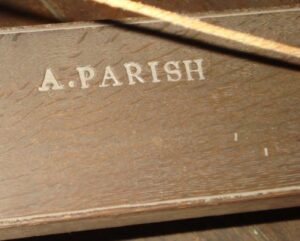

The spinning wheels at Raynham Hall Museum offer us a glimpse into the life and workmanship of Long Island’s early settlers, particularly its industrious women. Specifically designed to spin flax, this “Dutch-style” wheel (fig. 5) bears the stamp of Isaac Parish, an Oyster Bay woodworker. He, along with his brother Ambrose made countless spinning wheels for residents along Long Island’s north shore, from Glen Cove to Huntington². One entry from a Queens County daybook dated January 19, 1807, notes Isaac supplied Henry Hagner with six spinning wheels³. Features of this wheel include a foot treadle, bobbin, and distaff spindle to prevent long, unspun fibers from getting tangled. By stepping on the treadle to power the wheel, spinners would spin and wind thread on spools through the manipulation of fibers from the large distaff. Ambrose Parish crafted this circa 1800 wool spinning wheel mounted on an oak base (fig. 6). Large wool wheels (or “great wheels”), like this example, spun raw sheep’s wool by requiring the spinner to rotate the wheel while walking back and forth. If Winter Storm Lorraine proved anything, it’s that we should invest in a spinning wheel to pass the time inside and spin our own warm fiber creations!

- According to their shop records dating between 1766 and 1818, Nathaniel Dominy IV and Nathaniel Dominy V produced more than 293 spinning and winding wheels in addition to constructing carriage, wagon, and cart wheels. See link for more information: http://dominycollections.winterthur.org/wheelwrights/

- Isaac and Ambrose’s father, Townsend Parish, married Freelove Dodge, the daughter of another Oyster Bay woodworker Tristan Dodge, who is considered the maker of a ladder-back chair in the Raynham Hall Museum collection.

- Dean Failey, Long Island is my Nation (Society for the Preservation of Long Island Antiquities, 1998, 2nd edition).

Figure 1. Detail showing the process of producing linen. From William Hinck’s Views of the Irish Linen Industry (1791).

Figure 2. Wheelwrights at work. From Plate 1 of Denis Diderot, Encyclopédie, Volume X (1769).

Figure 3. Sampler by Rebecca Townsend, 1837. Silk on linen. Raynham Hall Museum.

Figure 4. Pocketbook with name and date, “Samuel Townsend EST 1755.” Linen, wool. Raynham Hall Museum.

Figure 5. Flax Spinning Wheel by Isaac Parish, Oyster Bay, 1790-1830. Raynham Hall Museum.

Figure 6. Wool Spinning Wheel by Ambrose Parish, Oyster Bay, ca. 1800. Oak. Raynham Hall Museum.

About the Author: Elizabeth Fox is the Marcia Brady Tucker Fellow in American Decorative Arts at the Yale University Art Gallery, where she is currently researching their collection of Connecticut furniture. She received her B.A. in History and Religion at Furman University and her M.A. in Decorative Arts and Design History at George Washington University’s Corcoran School of the Arts & Design.