Written by: Jessica Pearl

While recently moving archival materials to our new collections storage space, I found part of a well-known sketchbook in our collection inside a box. The section had detached from the binding due to age and ended up stored in a folder in a box, separated from the original sketchbook. Sometimes artifacts become disassociated from their data, proving how essential inventories are for museums!

I knew immediately that the pages came from Peter Townsend’s sketchbook¹. Within the detached section, I saw a drawing of a woman named Mary Yonge. The page says, “Mary Yonge, my washerwoman (from memory), Nassau 1825, Black.” We have very few visual representations of Black individuals at our museum, and none created by a Black individual. While the drawing is from memory and created by a white man, it helps visualize the lives of individuals during the 19th century.

The drawing of Mary is of her profile, showing her facial features and her headwrap. Her headwrap is functional and stylish, featuring a front tie at the crown of her head and drawing the eyes upwards. Headwraps are an African cultural trait that has remained in African diasporic cultures, including the Bahamian community to which Mary belonged.

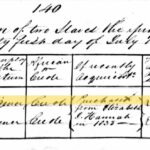

The drawing sent me on a deep dive to try and discover anything I could about Mary Yonge. Was Mary Yonge free or enslaved? Who was her family? With limited knowledge, I first searched the Former British Colonial Dependencies, Slave Registers, 1813-1814, but didn’t have much luck finding her in the 1820s. I did find a Mary enslaved by Ann Jane Lucretia Yonge in New Providence in 1834. It lists her as 36, mulatto, and a domestic servant. I then contacted the Bahamas Historical Society to see if they could help me. They were incredibly responsive and helpful and found that she may have taken the last name of her possible enslaver, possibly Henry Yonge². Whether or not she was enslaved or free, I can’t be sure.

Before the invention of the washing machine, doing the laundry was a difficult, labor and time-intensive job. It was a job that often fell to women; it required a particular set of skills, but not a formal education, and it was the type of work that was constantly in demand. If you had the income, you’d pay someone else to do this chore. Washerwomen first had to haul water from a water source, sort the laundry, boil huge tubs of water to soak and rinse the cloth, then move the items to another washtub where you would soap and scrub and agitate the cloth, and then rinse, squeeze, and dry. Not to mention the different methods of stain removal, such as chamber lye- stale urine! Given the hot, humid climate of the Bahamas, this was an incredibly demanding job. Oftentimes, there would be a communal aspect to the job, either getting family to help or working in groups, which gave women the opportunity to converse while working.

There is a history of washerwomen and laundresses depicted in paintings, engravings, and other art forms, something that Peter Townsend may have been aware of when he drew Mary Yonge. Situating the image of Mary Yonge within this tradition helps us to better humanize and understand the circumstances and conditions under which she lived.

- Peter Townsend’s (1796-1849) sketchbook is well-known because it contains the only known image of his uncle, Robert Townsend (Culper, Jr.). Peter was a doctor, published several medical works, and was among the founders of the Lyceum of Natural History and the New York Academy of Medicine. He was prolific in many areas; he wrote multiple volumes on his family history and was an avid artist. He spent 1823 to 1825 or 1826 in New Providence, Bahamas, and served as a doctor on the island.

- Henry Yonge was a Loyalist, a British lawyer who held the position of Attorney General in East Florida. He went to the Bahamas after 1783 (after the American Revolution), and served as an appointed clerk of the Council in Nassau, as a secretary, and as a notary. He received a crown grant of 400 acres on the island of Exuma. It’s likely that he brought people he enslaved with him from East Florida when he moved to the Bahamas.